A Brief History of Windows Profiles

The Windows user profile is a record of personal, user-specific data associated with a named user’s identity and desktop environment. It contains many elements, such as settings, configuration items, connections and history. User profiles have gone from their original, fairly simple format to one which is increasingly complicated, and maintaining integrity and reliability within the user profile is often a matter of concern to Windows administrators, architects and consultants. Preserving the user’s “personality”—which is contained within their profile—is often key to maintaining a good standard of user experience.

In the beginning…

Up until the advent of Windows NT, there was no such thing as user profiles per se. In Windows 3.x, users who shared devices were accustomed to fighting with each other over configuration items, filenames, and screen colors, among many other settings.

This wasn’t a very suitable solution for enterprises, and Microsoft was quick to recognize it as an issue. But with the arrival of Windows NT, the first true multi-user Windows system was born.

Windows NT 3.x worked in a very similar way “under the hood” as NT 4.0 did (apart from having to declare types for common program groups) with its user profiles stored in %systemdrive%\winnt\profiles.

Windows NT4, with the Windows 9x user experience, became much more popular than 3.x, which still ran on the old 3.x Program Manager interface, so even though it wasn’t the first, NT4 was probably most Windows administrators’ first exposure to the user profile itself.

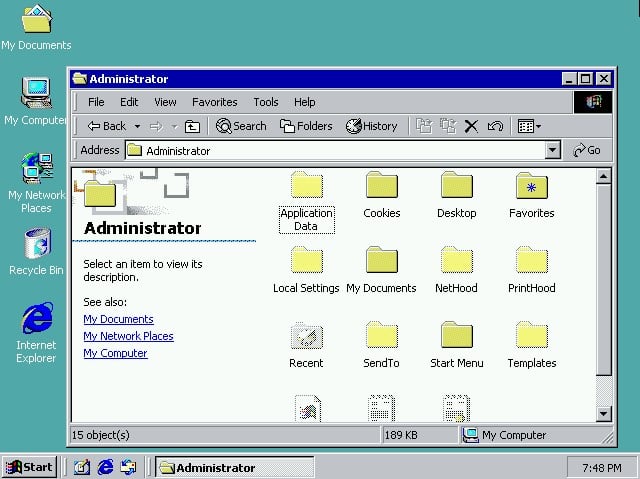

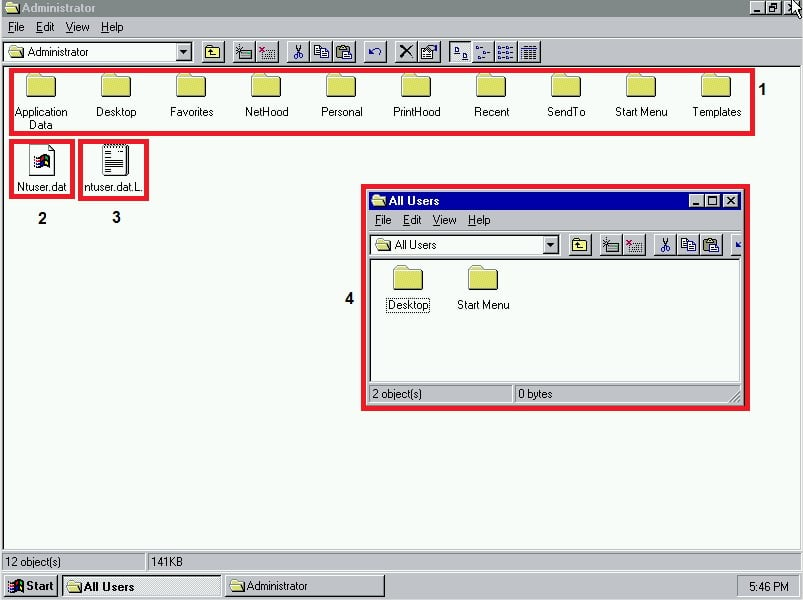

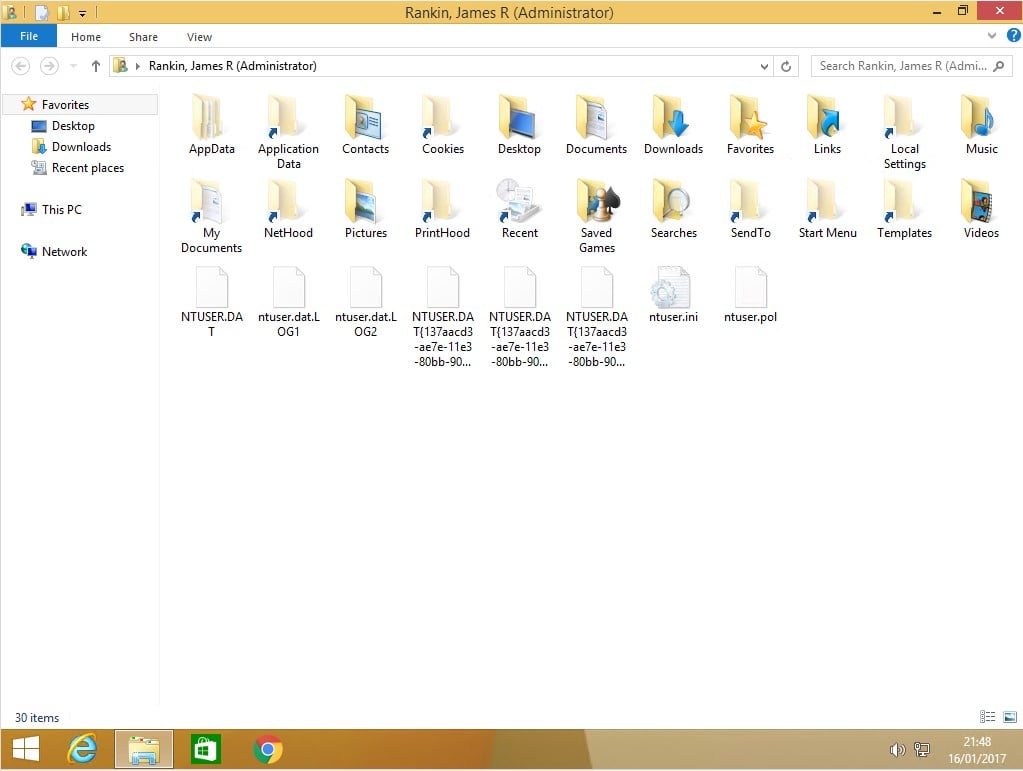

The Windows NT 4.0 profile could be mapped directly to a user environment variable called %USERPROFILE%, and the structure of the profile was composed mainly of these areas:

- The user profile folders, stored originally in %SYSTEMDRIVE%\winnt\profiles\%USERNAME% ([1] in the image below)

- The user’s Registry file, NTUSER.DAT, which maps to HKCU ([2] in the image below)

- The transaction log for the user Registry file, DAT.LOG ([3] in the image below)

- Shared settings that apply to all users (originally stored in %SYSTEMDRIVE%\winnt\profiles\All Users) ([4] in the image below)

This laid the groundwork for the Windows user profile as we know it, and the Windows versions that arrived since have continued to use this base profile template.

In addition to this, there were two special profile folders that complemented the profile itself.

We’ve already mentioned the All Users folder, which contains settings that are merged into each user’s individual profile, such as shortcuts on the desktop or Start Menu, but there is also the Default User folder. The purpose of this folder was to provide a base template for all users who logged onto the device, with a default set of configuration items that were copied into the new user profile.

At the time of Windows NT 4.0’s release, Windows 95 was the dominant force in desktop computing (having been released a year previously), and Microsoft quickly realized that allowing Windows 95 to support profiles in the same way would be essential to gaining enterprise traction. By enabling the “user profiles” option in Control Panel, Windows users could use the Client for Microsoft Networks (assuming an NT domain) to log in and henceforth maintain individual user profiles in much the same way (apart from slight differences, such as the Registry file being user.dat rather than ntuser.dat). Of course, Windows 95 didn’t have the same security features as NT Workstation, and the user logon prompt could be bypassed simply by pressing the Escape key!

Profile evolutions

As Windows versions progressed, the construct of the profile itself evolved. However, as applications were written to fit the profile structure of the time, shims and tricks also developed along with the profile to support legacy applications and to ensure that software was backwards compatible. A rundown of some of the more pertinent changes is listed below.

Windows 2000

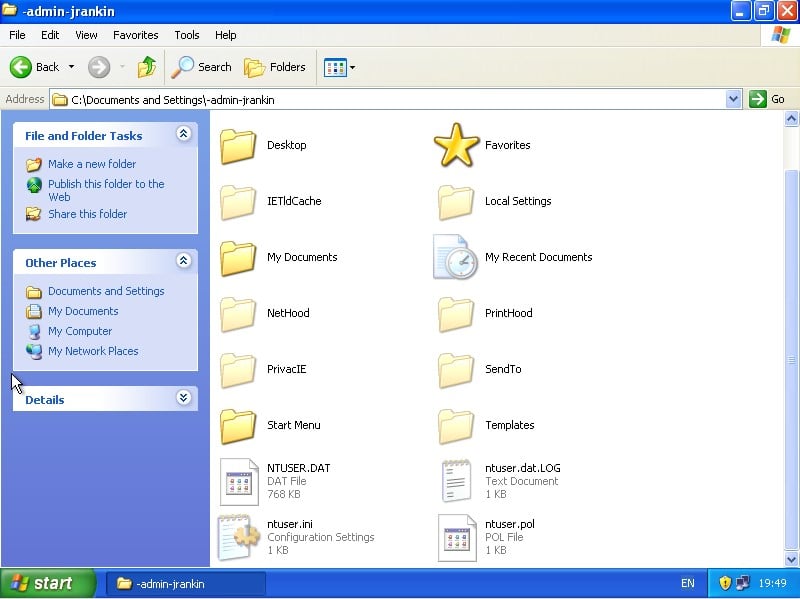

Windows 2000 moved profiles into a new folder, called %SYSTEMDRIVE%\Documents and Settings. The “Application Data” folder from the profile was mapped to an environment variable called %APPDATA%, designed with application developers in mind. The “All Users” area of the profile was mapped to another variable, called %ALLUSERSPROFILE%, again, to help out with development. A subfolder called “Local Settings” appeared in the user profile root, intended to hold data that wasn’t intended for roaming.

Windows XP/Server 2003

Most of the changes in Windows 2000 were continued into XP and Server 2003 without any particular additions, making Windows 2000 and Windows XP profiles for the most part interchangeable.

Windows Vista/7/2008/2008 R2

The big changes started with Vista and continued into Windows 7, with a raft of changes, and the very first “profile version” increment. This was understandable, as the Windows Vista/7 interface had made some radical alterations.

Changes-wise, this iteration of Windows saw a lot of churn profile-wise:

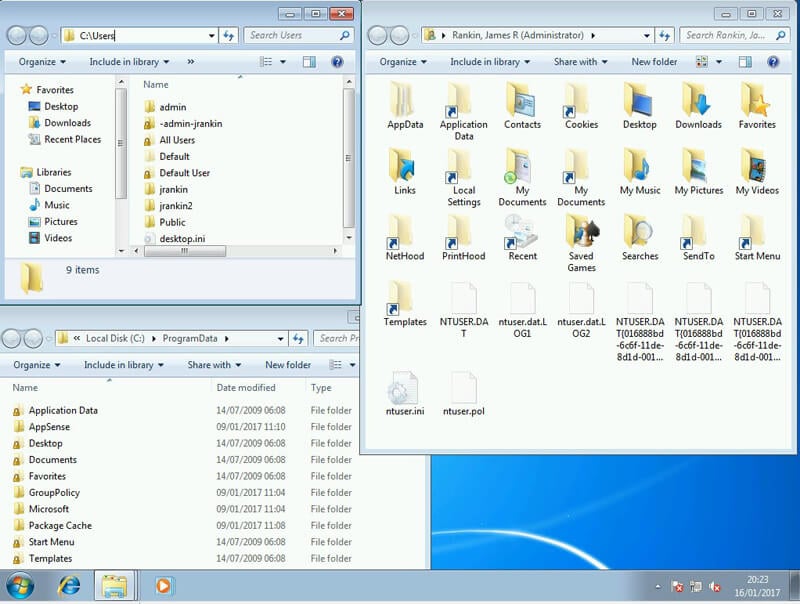

- %SYSTEMDRIVE%\Documents and Settings moved to %SYSTEMDRIVE%\Users

- “Default User” became “Default”, within the %SYSTEMDRIVE%\Users folder

- %USERPROFILE%\Local Settings was now moved to %USERPROFILE%\AppData\Local, and mapped to the user environment variable %LOCALAPPDATA%

- A folder called %USERPROFILE%\AppData\LocalLow was added, intended to house local application data that ran with a low integrity level

- %USERPROFILE%\Application Data was moved to %USERPROFILE%\AppData\Roaming and mapped to the user environment variable %APPDATA%

- %ALLUSERSPROFILE% was moved from %SYSTEMDRIVE%\Documents and Settings \All Users to a combination of %SYSTEMDRIVE%\ProgramData (for application information) and %SYSTEMDRIVE%\Users\Public (for shortcuts)

- Junction points (also known as symbolic links) were added for %SYSTEMDRIVE%\Documents and Settings, %USERPROFILE%\Default User, %USERPROFILE%\Application Data, and %SYSTEMDRIVE%\Documents and Settings \All Users to enable applications written on older platforms to still function, redirecting these locations to their new ones. Additionally, the SendTo, Start Menu, Templates, NetHood, PrintHood, Local Settings and Cookies folders within the profile were moved to new locations, and accompanied by further junction points to prevent application problems

- A Registry key containing profile-specific information was added to HKLM\Software\Microsoft\Windows NT\CurrentVersion\ProfileList with the user’s SID as the key name. Prior to this, locally-cached profiles could be removed simply by deleting the %USERPROFILE% folder, but now, the associated Registry key also had to be removed. Through the Windows user interface, this could only be done through the Advanced System Settings dialog

There was also the addition of the “.v2” profile type to consider.

Previously, when specifying roaming or mandatory profiles, only the path to the folder was expected. However, because of the large architectural changes between 2000/XP and Vista/7, the two profile types were incompatible. When a folder path was specified to a roaming or mandatory profile, on a Vista/7 endpoint, the actual folder accessed would have “.v2” appended to it by the system, in order to stop the inadvertent attempted load of the wrong profile type. 2000/XP were now considered “.v1” profiles, but the suffix did not need to be present when accessing a roaming or mandatory profile from these devices.

Vista and 7 also brought along the concept of the super-mandatory profile, which was a mandatory profile that would deny logon if the profile path was unavailable. This was triggered by giving the profile folder name a .man extension as well as the ntuser file itself.

Windows 8/8.1/Server 2012/Server 2012 R2

The next iteration of Windows brought some small changes, notably around the Windows Start Screen, which was captured into the profile in %LOCALAPPDATA%\Microsoft\Windows\appsFolder.itemdata-ms. My Documents also became Documents in the profile root.

Originally, Windows 8.x would convert .v2 profiles into a compatible state and maintain the .v2 suffix, but, due to issues when roaming between newer and older endpoints, a Microsoft hotfix was made available to remove this functionality and force Windows 8 to use a .v3 profile (or Windows 8.1 to use a .v4). The reason for the incremented version from 3 to 4 was most probably to do with the architectural changes required to enable the “WinX” right-click Start Menu that was built into Windows 8.1 but did not appear in Windows 8.

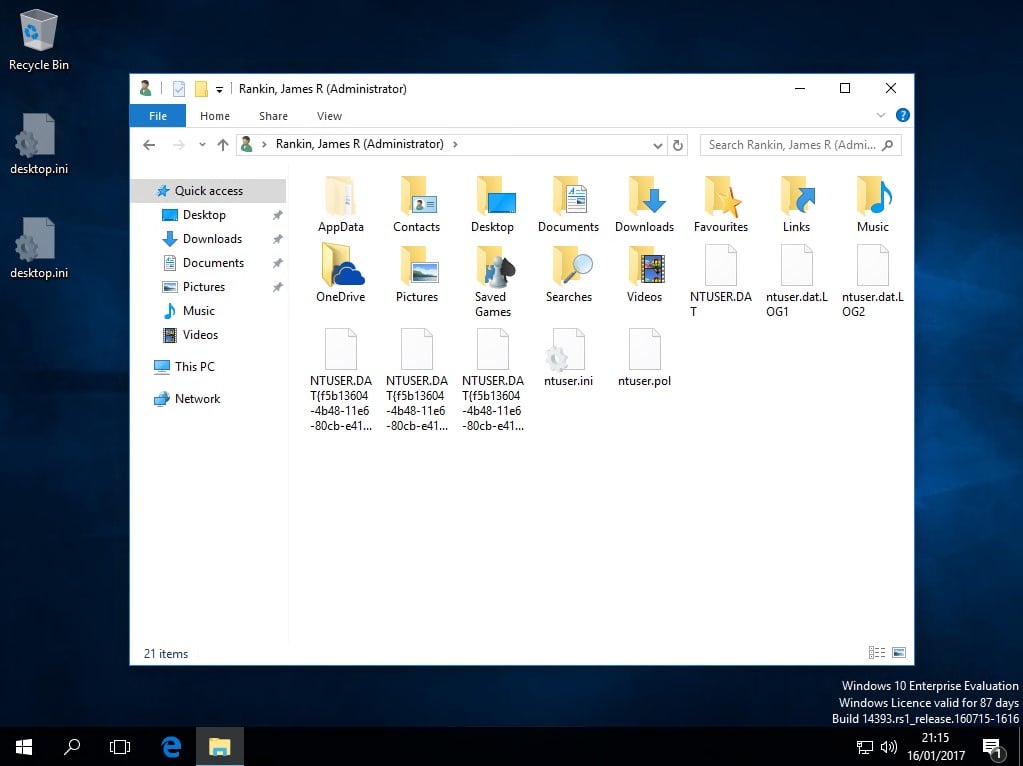

Windows 10/Server 2016

Windows 10 brought some further changes, most notably the addition of databases within the profile to support the new-look Start Menu, the Notification Center, and Internet Explorer cookies (although the Cookies database actually debuted in IE10, rather than a specific Windows version). Microsoft’s UWP (Universal Windows Platform) apps now sit within the user profile, installed to %LOCALAPPDATA%\Packages. There is also now a OneDrive folder by default in the root of the profile, although this can be disabled and removed by Group Policy. Also worth noting is that many of the junction points to support backward compatibility have finally been removed.

Most notable about Windows 10, however, is that the “profile version” increments can now happen with Windows 10’s feature upgrades. Windows 10 version 10240 launched with a profile version of .v5, which was expected due to the radical changes observed on the Start Menu. However, the Anniversary Update (version 14393) moved from a .v5 to a .v6 profile version, which took many by surprise. Some websites reported being able to actually simply rename the .v5 to .v6 and the profiles behaved normally, but Microsoft’s own documentation makes clear this is not a great idea. “Incorrectly versioned profiles may be missing default profile configuration information that is expected by the operating system, and could contain unexpected values that are set by a different operating system version. Therefore, the operating system will not behave as expected. Additionally, profile corruption may occur.”

It’s not clear what set of circumstances or under-the-hood changes will make Microsoft increment another profile version in future, but it is clear that this is a real possibility. Reviewing profile version types within the Windows Insider flights is recommended to stay abreast of possible further change.

Profile sizes and performance

Unsurprisingly, the average user profile size has increased exponentially over the years, rising to approximately 800 times bigger when measured from Windows NT4 to Windows 10. Windows 8 to 10 saw the biggest jump in total (more than 60MB), but NT4 to 2000 was the biggest in raw percentage terms.

Interestingly, Windows 10’s initial profile creation time remains the longest out of all the Microsoft operating systems to date, which is mainly due to the “provisioning” of the Universal Windows Apps from within the base image.

| OS | Profile Size (MB) |

| Windows NT4 | 0.15 |

| Windows 2000 | 7 |

| Windows XP | 11 |

| Windows 7 | 20 |

| Windows 8.1 | 61 |

| Windows 10 | 123 |

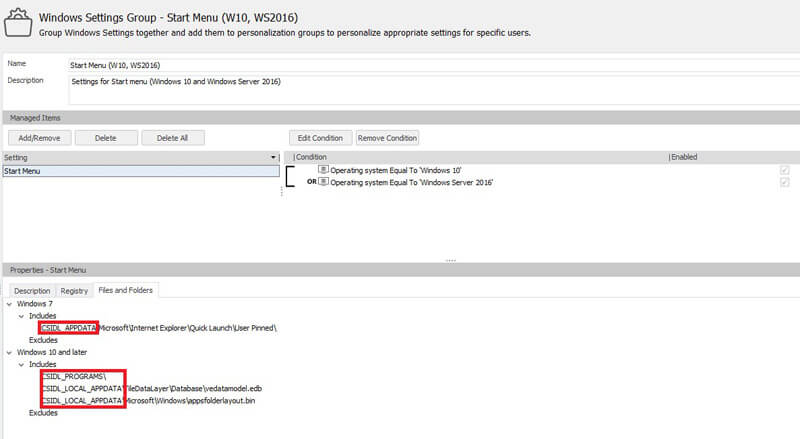

KNOWNFOLDER ID and CSIDL notation

Microsoft has tried to help developers by encouraging the use of what was originally called CSIDL (Constant Special Item ID List) notation, and which since Vista has been called KnownFolderID. They are designed to identify special folders used frequently by applications, but which may not have the same name or location on given systems. For instance, the CSIDL_PROFILE or FOLDERID_PROFILE versions of this can refer to %SYSTEMDRIVE%\Users\%USERNAME% on Vista and above, and %SYSTEMDRIVE%\Documents and Settings\%USERNAME% on older operating systems.

Ideally, all applications would subscribe to the usage of KnownFolderID, but unfortunately, not all applications are from an ideal development world. In some cases, it can be extremely challenging to maintain settings across all endpoint types from all applications because of the inconsistent behaviour of some software (particularly legacy).

You can read more about KnownFolderID and CSIDL via the links here.

Managing profiles

Managing profiles can be easy – if your users don’t roam from device to device, and you use the same operating system version everywhere across your estate. However, this is rarely the case. Even if your users have no roaming or hot-desking requirement, device failure or reimaging can mean that maintaining user configuration settings is a necessity. And with Windows 10, the possibility of multiple operating system versions becomes very real thanks to the aggressive update cadence of CB and CBB. Muddying the waters further is the possibility that your users connect to applications or desktops hosted on RDSH or XenApp instances, where the operating system could again be different, and henceforth, the profile version.

AppSense Environment Manager (and in particular the Personalization Server feature) is one of the most effective tools for managing multiple Windows profile versions, allowing smooth and seamless roaming of user settings across operating systems old and new. The EM Personalization Server has always used the CSIDL/KnownFolderID methods mentioned in the previous section, allowing application settings to be portable across profile versions with a minimum of administrative overhead. Additionally, operating system-level settings are captured and restored on an OS-specific basis, meaning that Windows 10-specific settings would never be applied to a Windows 7 desktop. But settings that can persist between OS versions (like the desktop background, for example) would be applied, bringing a uniformity to disparate user sessions that is difficult, if not impossible, to achieve with standard roaming methods.

AppSense EM Personalization Server and the abstracted settings capture that makes it completely independent of profile versions

There are a lot of profile management tools and methods available, but if you need to allow users to operate flawlessly between Windows operating system versions or different feature upgrade levels within Windows 10, AppSense DesktopNow Environment Manager should always be a product to consider. Additionally, it eliminates the risk associated with Windows 10 feature upgrades, should a profile version be incremented in the new release – EM will simply keep on working as if nothing had changed, reducing the resource and overhead required to deal with the version uptick.

Summary

The Windows profile has changed a lot down the years, most notably between Windows XP and Windows Vista. Maintaining the user personality whilst at the same time allowing the enormous back catalog of Windows enterprise applications to function has required a lot of architectural modifications and under-the-hood tweaking. With Windows 10, profile management becomes even more of a headache, combining masses of locally-cached data with a versioning system that can be changed during any given servicing window.

If you want to extricate yourself from the twisted maze that profiles represent, then choosing a tool that abstracts these settings away should be one of your primary considerations. Making the right choice will allow you to forget about what changes are coming from the next iteration of Windows profiles, and concentrate on using IT to enable your business.

About James Rankin

James is somewhat of a legend in the Windows and AppSense community, and an authority on Windows 10 migration. He has delivered a series of posts on his own blog (http://www.htguk.com/blog/), covering what does and doesn’t work, as well as improvements Microsoft has made over the last 12 to 18 months that enable IT to deliver a better migration.

James is based in the North East of England and is an independent consultant who frequently works with AppSense products. Email him at: [email protected].